Celtic ‘is a magic bag, into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come.”

– J.R.R Tolkien

We, by and large, are a nation descended from immigrants. The people who, by choice or by force, left behind the land of their birth and crossed a dark, endless ocean to come to a land which they did not know. Many did not stop there. They trod through an unfamiliar country, seeking a place to put down roots and make a better life for themselves and their children. No matter what year they landed or what country they came from, every single immigrant shares this story of doubt and hope.

For those of us who claim a Celtic ancestry, this backstory can often turn into a stock explanation with the assumption that one’s ancestors came over during the Famine. It’s not unlikely, considering that over 1.5 million Irish came to America during this 10-year period and quickly spread out to form communities that continue to the modern day. However the concept of ‘Celt’ does not begin nor end with the Irish. Their history is as vast and diverse as the stars in the night sky.

The Ancient Celts

The Celts did not have a written history. Their stories were passed down through an oral tradition that was wiped out with the conquest of Gaul. As such we are left searching through the mire of historians from other countries to figure out the details. Like many ‘historical’ accounts of the era, poetic mythic, biased thinking, and accuracy were often tangled together. So it pays to have a skeptical eye when researching. Thankfully we have modern anthropologists and sociologists who can help narrow things down.

Going back around the year 1200 B.C.E., the Celts were much less homogeneous than we think of them now. They were tribal folk, their people spread out through most of Europe from Iberia to Ukraine, Gaul, and across the ocean to the Island of the Britons and Picts. Their presence was known in Greece, Portugal, and even as far as Turkey. The Celts shared similar languages, belief systems, and social traditions that kept them connected long before they began trading with the larger world.

Often known as the Keltoi by the Greeks, it is important to note that at this time the tribes were not unified under one state, nor were they a singular ethnic group. Generally, we attribute the Gauls, the Celtiberians, the Gallaeci, the Galatians, the Lepontii, the Britons, and the Gaels to be a part of the greater Celtic cultural grouping. There were many larger clans under a tribal chieftain, under which smaller ones shared familiar cultural crossovers such as language, religion, and burial practices. Given the berth of their territory, one can also find an overlap with early German, Iranian, and Slovakian cultures.

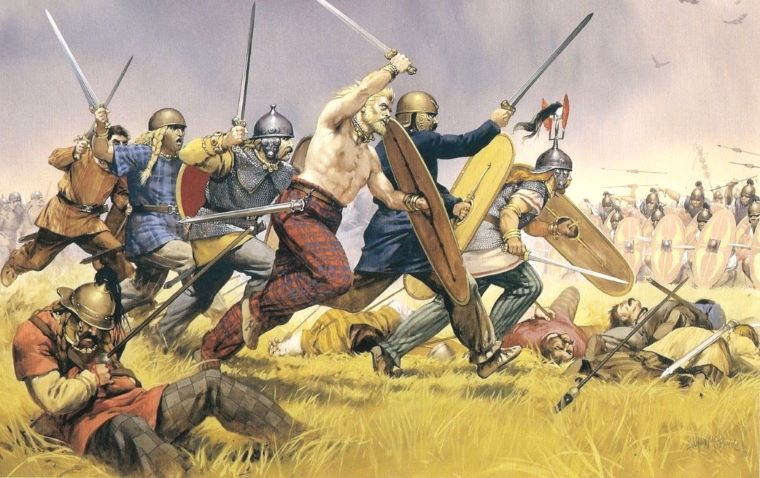

To many contemporary cultures, the Celtic tribes were considered ‘barbarians’. Their battle prowess was a subject of fear and admiration among their enemies, and they were often hired as mercenaries throughout the Mediterranean. They were said to be tall, ferocious-looking folk whose passions ran high in all things. The women of the Keltoi, though still generally bound by a social hierarchy, could still hold positions of power such as tribal leaders, druids, and warriors. To the Greeks and Romans, who had a far more limited perception of what women ought to be allowed, this was downright shocking.

However, these tales overlook the artistry and skill developed by the culture. Archaeological evidence shows the remains of brilliant metalwork found in grave sites, showing off complex and highly detailed jewelry designs. Their weapons and armor were of considerable quality, enough to make them a dire threat in warfare. They were weavers and dyers, the bold multicolored cloth worth remarking upon even by their enemies. The Celts were considerable traders of their time, bartering amber, silver, and furs in exchange for Greek wines and colored glass. Their salt was especially sought after, as it was a necessity for preserving meat across the world.

Despite their incredible influence and territory, the Celtic lack of unity was to be their downfall. After five centuries of off-and-on warfare against Rome, Gaul was eventually conquered by Julius Cesar in 58 – 50 B.C.E. His military campaign left the Celtic people so open to attack that they suffered further attacks from the Germanic tribes, Slavs, and Huns during the Migration Period from 300 – 600 A.C.E. By this point, few if any, people still identified as Celts, as the culture and language that bound them had been thoroughly quashed.

Modern Celtic Heritage

After reading this you might after yourself how, almost 1,500 years after the fact, anyone could still claim a Celtic heritage?

The general identification of the Celtic nations in the modern sense includes Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, and the Isle of Mann, though Galicia and Portugal are sometimes included depending upon who you ask. Some even consider the Nordic countries to be close cousins given the shared history between their peoples. The revival – or renaissance – of Celtic cultural interest didn’t really begin to take hold until the 1900s. During this time there was a vested interest in the long-vanished aspects of the once prominent Celtic people.

This was the post-Industrial Revolution era. The world was slowly getting smaller, and modernization had taken hold of every corner. For many, tradition and progress were at war, which more often than not leads to a romanticized ideal of the past when things were ‘simpler’ and ‘better’. Writers and artists latched on to this concept as inspiration for their work, although not always in the most positive manner. Though imperfect. this interest did lead to a vested effort to research and preserve what existed as well as renew the artistry through modern methods. Painters utilized famous legends such as Tristan and Isolde as the subject of their work. Celtic motifs became popular, being utilized for everything from architecture to pottery.

If you grew up anywhere between the early 90’s and the millennia, I’m sure you recall the New Age sensation of singer/songwriter Enya. This Irish musician, whose real name is Eithne Pádraigín Ní Bhraonáin, was the start of a whole new wave of fascination with the Celtic aesthetic in popular culture. In the same decade, the step-dancing phenomenon of Riverdance gained sweeping popularity with its mesmerizing large-scale production. During this time, Celtic and Irish festivals began to take hold, with many cities boasting high Irish/Scottish populations offering enthusiastic participation to the crowds. Everything from music, food, clothing, and Highland games are showcased, mimicking the ancient pagan festivities that once took place in pre-Christian Europe. As with any cultural event, these fests are means to be a shared experience, bringing people together to share in the mutual expression of heritage.

As a nation made up mostly of immigrants – many of whom have never traveled to their ancestral country of origin – there is a sense of cultural dysphoria within the U.S. We crave connection to one another, a sense of history and understanding that all too often is denied in the wake of perfect Americanization. We’re mutts. We are a patchwork quilt of heritage and history, each panel telling a bold, colorful story of the people who came before that made us possible. Looking back, we tend to pick which panel is our favorite and attach our identity to it. We look for meaning. We thrill at the potential to learn and explore a side of ourselves that may have been unknown before. This isn’t a bad thing. Far from it. People need community. And for those of us who identify under the truly massive Celtic tapestry, the bigger community means a greater opportunity to make a meaningful connection.