Winter in England was no joke, especially in the more rural communities. Seaside villages were buffeted by storms and many country villages were isolated from the larger cities when the weather was bad enough. Hard frost, freezing rain, and deep snows sometimes lasting well into April. Difficult traveling conditions often kept people at home, or at the very least limited to their villages and local communities. Long months were spent indoors living off the supplies they had harvested in the previous portion of the year.

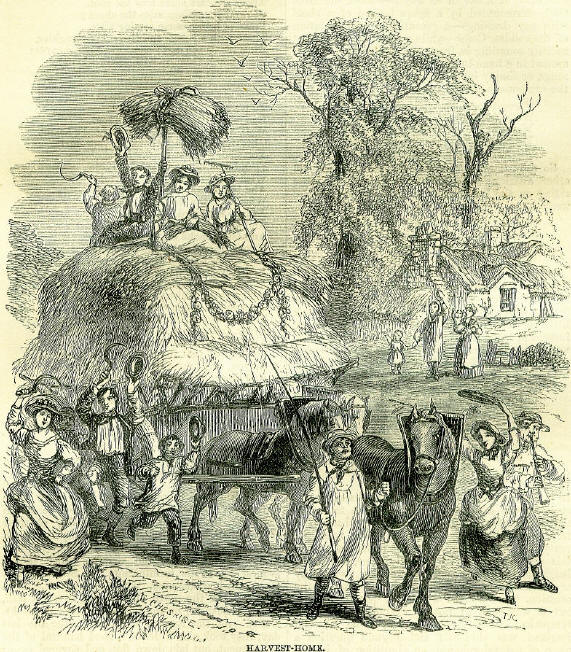

Harvest. We don’t think much about it these days unless you’re part of a farming family. And even then, it doesn’t carry the same connotation it used to. The harvest is about so much more than reaping the fields and the last heavy work that has to be done before the change of the season. Once the work was finished, there was a brief period during which people could relax and enjoy the company before the snow set in.

For much of English history Catholic feast days dominated the celebratory life of its people. During the Elizabethan era the Protestant religion had taken hold, and while Catholics were tolerated under Elizabeth I rule, they were not exactly loud about their beliefs. The holidays celebrating the saints fell out of popularity to some degree. However, the church was still a large part of communal life and many celebrations still centered around the church in some manner.

Harvest seasons usually began around August with Lammastide wherein folk would take fresh wheat and make loaves, giving them to the church as communion bread. Festivals would last through the autumn seasons, allowing people the opportunity to celebrate as they finished their work. Harvest celebrations ended roughly around October or November and the people, of course, offered up their thanks for the bounty the season gave them. This would often end with a tradition known as the “Mell-supper”. The final patch of wheat left standing in the fields was also called the “mell” or “neck.” Its fall marked the end of the harvest season.

Mell-supper: A harvest supper. So called from the French “meler” (to mix together), because the master and servants sat at the harvest table together.

The Mell-supper is a carryover from the old pagan times. Farms would hold feasts where they would cook and dance together with their workers. It celebrated a kind of reverence for the work that was done, and for a brief time master and servant sat and dined with one another as relative equals. Corn dolls were made and people would make a real party of it.

Common foods for the feast were cabbage and onions, but as excursions to the Americas brought forth new produce, there may have been potatoes and tomatoes as well. The poor sourced their meat off the land, taking advantage of the small birds (partridges, ducks, and pigeons) and the fishing available to them. Bread was a constant source of nutrition, being far more grainy and darker than our modern white bread. Ale was drunk liberally, but it’s important to remember that the ale of the time was not particularly alcoholic. The wealthy of course had a great deal more variety available to their table, but when one considers harvest festivals we tend to think of the people responsible for producing the bounty, not those who get to take advantage of it.

After the Protestant reformations began, many Church holidays were done away with, taking with them the burden of the local population of having to pay for such celebrations. They were replaced by some degree with Days of Fasting and Days of Thanksgiving. In fact, there was a Day of Thanksgiving following the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 as well as one following the infamous 1606 Gunpowder plot which would later develop into Guy Fawkes Day, still celebrated today.

The combination of harvest celebrations and popular holidays carried over in the minds of the people. To this day we still celebrate a watered-down iteration of the old harvest festivals. While the means have been changed and in many cases widely debated as to whether or not it has any place in modern society, for my part I think there is something to maintaining an understanding of where our food comes from and that its bounty is not endless.

Authentic Renaissance Cooking

Cookbooks have survived from the 16th century, but are often very hard to reproduce food from. This is not only because middle English was still transitioning to modern English and the standardization of spelling had not yet been completed, but also because it was written for a very different kitchen than the one in your home. Cooking was done over a fire, thus no cooking times or temperatures. There were no standard measurement cups or scales, thus no exact measurements. Renaissance cooks were instructed to cook things until “done” or add as much spice as to “make a small hill.”

Let’s look at one recipe from “A Propre new booke of Cokery” from 1545

To make pies of grene apples.

A Propre new booke of Cokery – 1545

Take your apples and pare them cleane and core theim as ye will a Quince / then make your coffyne after this maner / take a little faire water and halfe a disshe of butter and a little safron and set all this vpon a chafyngdisshe till it be hote / then temper your flower with this vpon a chafyngdissh till it be hote then temper your floure with this said licour and the white of two egges / and also make your coffyn and ceason your apples with Sinamon / ginger and suger inough. Then put them into your coffyn and laie halfe a disshe of butter aboue them / and close your coffyn and so bake them.

TRANSLATION: To make pies of green apples. Take your apples and pare them clean and core them as you would a Quince / then make your coffin after this manner / take a little fair water and half a dish of butter and a little saffron and set all this upon a chafingdish till it be hot / then temper your flour with this upon a chafingdish till it be hot then temper your flour with this said licquor and the whites of two eggs / and also make your coffin and season your apples with Cinnamon / ginger and sugar enough. Then put them into your coffin and lay half a dish of butter above them / and close your coffin and so bake them.

Coffyne/Coffin: A very thick pastry crust complete with a pastry lid that the pie filling would be cooked in. Pie filling would often be scooped out of the coffin to eat and the coffin would be reused to bake more pies.

Renaissance Inspired Cooking

Want to try recipes that are inspired or adapted from the Elizabethan era but suited to your modern kitchen? There are many books available on the market or free websites offering recipes featuring authentic ingredients and flavor profiles. Try these recipes from Historyextra.com

Want to learn more about Tudor Food?

Sources

Feature image: The Corn Harvest, Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1565

Mell Feast to Michaelmas-historyextra.com

Harvset supper – Theoldfoodie.com

WEATHER IN HISTORY 1500 TO 1599 AD-premium.weatherweb.net